NeuroLogic

December 1, 2017

Many patients start out with occasional “charley horses” in their legs or spasms in their backs. But eventually, these relatively mild symptoms progress to extreme rigidity and spasticity throughout their bodies, leading to gait and mobility issues that prompt dangerous falls. After multiple appointments with specialists, and often years after the onset of their initial symptoms, some of these patients end up in the office of Johns Hopkins neurologist Scott Newsome with a diagnosis of stiff person syndrome.

Stiff person syndrome is truly a “one in a million” disease, explains Newsome. Because of this extremely rare incidence, he adds, clinicians know little about the best ways to treat it.

That’s why he and his colleagues recently decided to launch a center for this disease within Johns Hopkins—which sees more patients with this disease than any other medical institution in the world—to both treat patients and to study them with the goal of developing better treatments in the future.

To reach the diagnosis of stiff person syndrome, Newsome and his colleagues run patients through a comprehensive battery of tests, both to look for distinct signs of this condition and to rule out other diseases that can present in a similar way. Besides a physical exam and history, the team often performs electromyography, MRI, lumbar puncture, a malignancy workup, and blood tests.

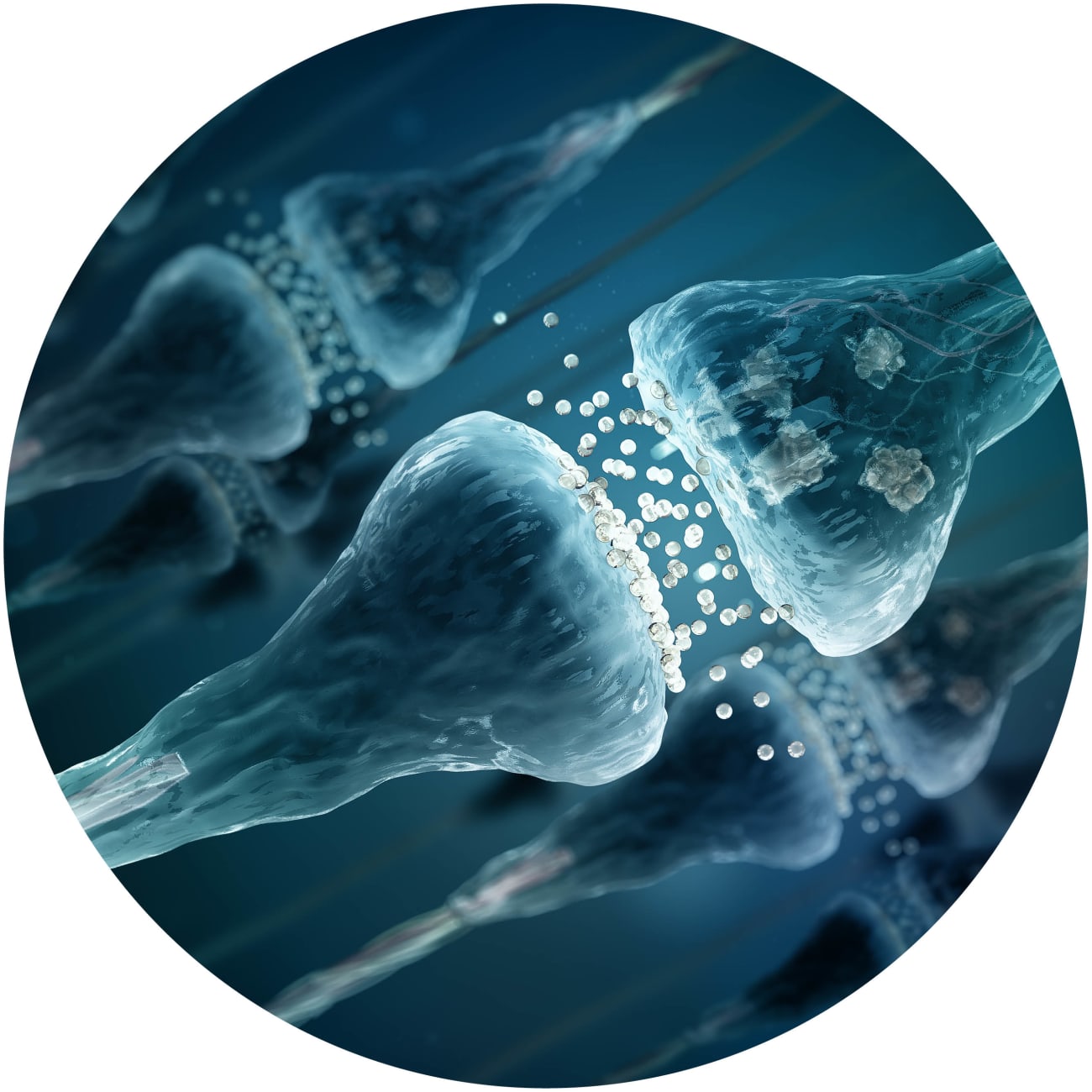

One telling result is a positive test for anti-GAD65 antibody, an antibody against an enzyme that helps process glutamate to the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA. About 80 percent of patients diagnosed with “classic” stiff person syndrome have this autoantibody, thought to be a key factor in its pathogenesis. Many treatments for this disorder, such as GABAergic agonists or immune-modifying therapies such as intravenous immunoglobulin, are aimed at combating this possible cause. Other treatments, such as acupuncture, aqua therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy, address chronic pain and other symptoms that can greatly reduce a patient’s quality of life.

Finding a way to shut off this autoimmune response is a fundamental goal for Tory Johnson, a researcher in the new center whose work is focused on autoimmune central nervous system diseases. Taking advantage of the large cohort of stiff person syndrome patients seen at Johns Hopkins, she and her lab are currently working on a project to characterize the exact epitopes that each patient’s immune system recognizes and develop a methodology to turn off that harmful response, all while leaving the rest of the immune system intact. She and her lab also plan to search for other autoantibodies that could be responsible for this disease in the minority of patients who aren’t anti-GAD65 antibody positive.

Using this combined research and personalized medicine approach, Newsome says, is pivotal for achieving the best outcomes now and in the future for this disease. “This is the first and only stiff person syndrome center in the world,” he says. “At the end of the day, everything we do here will strive for improving lives for people with this condition.”

To refer a patient, call 410-614-1522