Johns Hopkins Orthopaedic Surgery

December 10, 2014

It’s not surprising, says Lynne Jones, that patients diagnosed with osteonecrosis of the hip want to know about stem cell therapy. These patients are typically in their late 20s to 50s when they learn that their hip pain is due to decreased blood flow to the bone and that the disease can progress to debilitating bone and joint breakdown.

Jones heads Johns Hopkins’ Center for Osteonecrosis Research and Education, and says it’s true that stem cell therapy holds considerable potential as a precollapse approach for osteonecrosis. But in helping patients understand their options, Jones is clear. Although a few stem cell studies have shown promise, she says, “in general, it’s still unproven. We are engaged in research to determine the best way to utilize stem cells for the treatment of this disease.”

In a 2014 study to understand which treatments are being used, Jones and colleagues found that between 1992 and 2008, the number of procedures performed for osteonecrosis of the hip nearly doubled. Furthermore, out of the 6,400 procedures performed in 2008 for osteonecrosis of the hip, 88 percent were total hip replacements and 12 percent were joint-preserving operations. In the United States, joint-preserving interventions such as partial joint arthroplasty and osteotomy have fallen from favor while core decompression has become the most prevalent precollapse treatment.

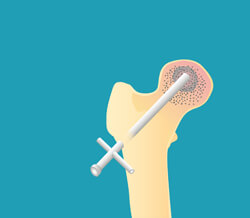

In the 1960s, French doctors Paul Ficat and Jacques Arlet first performed a core decompression as a biopsy to verify osteonecrosis. As a result, patients experienced pain relief, and the doctors hypothesized the core relieved the pressure that caused the pain.

One of the people Ficat and Arlet trained was orthopaedic surgeon David Hungerford, who came to Johns Hopkins in the 1970s and introduced core decompression to the United States.

“Since that time, core decompression has been fairly successful in patients with early-stage disease or with small to mid-size lesions,” says Jones. “At Johns Hopkins, we have helped develop a short MRI sequence for diagnosis of early osteonecrosis, which is important for being able to offer patients a joint-preserving treatment option.”

After a core decompression, patients are usually out of the hospital within 24 hours. Pain may recur in some, but the procedure can be repeated.

“For patients between 20 and 50 years old,” says Jones, “a core decompression can provide pain relief and delay the need for a hip implant for several years.”